Proof of Work (PoW) and Proof of Stake (PoS) are both consensus mechanisms used in distributed networks, like cryptocurrency networks, to collectively come to an agreement. In other words, they are ways for everyone in the network to agree on all the transactions that take place within it. There are other consensus mechanisms like Pure Proof of Stake, Proof of History, and Proof of Time, but I’ll be sticking to PoW and PoS, and more specifically Bitcoin and Ethereum, because they are the most important and the most relevant.

Yet regardless of which consensus mechanisms are used, they all aim to maintain the integrity of transactions and the overall security of the network so bad actors can’t get away with double spending coins or approving fraudulent transactions.

They’re called consensus mechanisms because they are a means to come to a consensus. Having a reliable system for verifying and approving transactions (coming to a consensus) is essential to any monetary network functioning. Nobody would be able to use—let alone want to use—a monetary system if people were always spending other people’s money or the value held within that system was constantly at risk of theft.

In a centralized system, the consensus mechanism is the centralized authority or administrative body governing it like a central bank, CEO, or other small group of people, but that doesn’t work if you are aiming for a decentralized way of governing and approving transactions. Thus, PoW and PoS emerged as ways for cryptocurrency networks to maintain the integrity of their transactions without relying on a central authority like a company, bank, or government.

Now that you have a basic understanding of what a consensus mechanism is and why it’s important, let’s transition to a deeper look at PoW.

Proof-of-Work

While the Bitcoin network is the most widely referenced example of PoW, it’s important to remember it’s not the only one, and I don’t just mean in crypto. Bitcoin may be the PoW poster child and its particular iteration of PoW may be unique, which is why I’ll discuss it in detail later, but PoW, in its basic form, simply means that something demonstrates or requires human effort or work.

PoW is what any employer demands of their employee before payment, or what necessarily goes into the extraction of something like gold from deep underground. Goods and services take time, effort, and money to create or accomplish, so there are certain costs baked into their ultimate value.

The work put into a task or system is also a way of ensuring positive incentives because wasted energy has very real economic consequences. PoW, then, is not a concept created by the crypto industry—though it certainly sparked a new innovative version—it’s just a method for earning and ascribing value.

If there is effort or work that goes into creating something, that good or service should at least be as valuable as that effort. This is a pretty intuitive concept, but it’s so fundamental to how we value anything that it either goes nameless or just isn’t attached to the specific phrase “Proof of Work.”

Take someone who is an avid exerciser as an example. The physique they earn through countless hours of exercise is clearly a product of hard work—work that most people would agree has given them something of value. There is no way to get that value without the work. Whether it’s abs or gold, the only way you’re getting either is with some serious effort, and that is a major factor in why they are valuable in the first place.

Though value is largely, if not entirely, subjective, there’s no escaping that some things require a great deal of effort to create, extract, or perform and that has to be factored in if we are to have any rational approach to deciding what a “subjective" value is. Nobody would work hard to get abs if it didn’t provide at least as much value as the effort required to get them, and nobody would dig gold out of the ground if they couldn’t sell it for at least as much as the extraction cost.

Now, this is not to say that anything that requires effort has value. Just because you spent 30 hours knitting a sock doesn’t mean someone is going to pay you for it. However, time, effort, and money put into something are the most obvious considerations when deciding how much that thing is worth. If you can’t at least get the value of your effort or money back, the basic laws of economics will eventually deselect whatever it is you’re making or doing over time.

However, if whatever it is you do or make provides enough value to justify its costs, then there is a PoW element baked into your cost structure other people are probably acknowledging. I want to emphasize this because, as I transition to Bitcoin, I want to disabuse anyone of this notion that PoW is a new idea or too energy intensive.

Without the energy, the effort, and the work, most things would either be nonexistent or considerably less valuable. In other words, the energy put into them is either necessary or a crucial component to them having value. If anything, the more energy put into it, the more valuable it probably is. And, as mentioned, the laws of economics would eventually do away with anything that wasted energy for no reason.

In this case of Bitcoin, energy secures the network, so more energy adds more security, which could be thought of as providing more value to the system. Work and energy are what make the world go round, so it should come as no surprise that things of value take work or energy to create or maintain—the work is the proof.

With that out of the way, let’s transition to Bitcoin’s specific iteration of PoW.

Bitcoin

In the Bitcoin network, PoW refers to a competition between miners to solve cryptographic puzzles. I’m sure that will sound silly to some, but let me explain. Though people running mining operations generally call themselves miners, the term also refers to the computer systems (mining rigs) that run the network. So when I say miners solve cryptographic puzzles, I’m essentially saying computers are competing to solve a problem.

This process is commonly referred to as mining because the energy and resources required to solve the puzzle are analogous to the real-world process of mining precious metals from the earth. Just like real mining takes energy to get gold out of the ground, mining new bitcoins takes a whole lot of equipment and energy.

To get a little more granular, each Bitcoin mining rig is essentially working to guess a really long number (or hash). But because there are so many permutations for such a long number, an incredible amount of computing power is needed.

A helpful analogy for understanding this process is a lottery system. Each computer is able to buy a small number of lottery tickets at a time, so the more computing power (lottery tickets) you can buy, the better chance you have of solving the puzzle and winning the block reward (winning the lottery).

If you’re a mining company or group of miners with about 10% of the hash rate, you’ll win the block reward roughly 10% of the time. Just keep in mind that the Bitcoin lottery is constantly running so the odds really do balance out over the long run in a manner proportionate to the computing power you contribute to the network.

And as a side note, the difficulty level for solving these puzzles will change every two weeks as miners join and leave the network. This is known as the difficulty adjustment and just ensures a consistent amount of time (roughly ten minutes for Bitcoin) is taken to solve a block regardless of the total amount of computing power competing to solve any given puzzle, but I digress.

So, miners are really just high-powered, specialized number guessers, and the reward for guessing that number is they get to approve the next block on the blockchain and collect the block reward, which would reimburse them for the energy the mining rigs used to solve that block.

At this point, you might be asking how this makes any sense. Well, the purpose of this structure is it forces miners responsible for approving transactions to have skin in the game. Each miner has to spend real money (energy) to solve these puzzles and approve blocks, so they are incentivized to act honestly and collect the block reward to reimburse them for the very real energy they expend.

If a miner pays for all that energy, wins the opportunity to approve a block, and then approves illegitimate transactions, they won’t earn their reward, meaning they just wasted all that energy (money). This financial incentive is what secures the network by ensuring only those who have expended resources (put in the work) are granted the right to approve a new set of transactions on the blockchain.

Now, in the early days, Bitcoin mining was easy to run and only required a basic laptop, but now it requires pretty expensive gear that isn’t exactly accessible to everyone. The level of energy and computing power needed to have a realistic chance of approving transactions is also incredibly out of reach for any one miner or even a small group of miners.

This is definitely a reasonable critique of Bitcoin, as it falls victim to the economies of scale where larger centralized buyers can lower their costs and smother smaller players out of the market by disproportionately increasing their share of the computing power with those lower costs. The lower cost associated with larger operations and the tendency toward centralization of the mining hardware is arguably the weakest point of PoW systems like Bitcoin.

This is an unfortunate reality, but it’s important to note that, one, individual miners can join mining pools to collectively pool their hash rate with other miners so they all have a real shot at earning block rewards, which lessens the extent to which economies of scale shift the balance of power in the mining part of the network.

There is still a large barrier to entry when it comes to the overhead of purchasing mining rigs and other equipment, but mining pools at least balance the power of large centralized miners within the network to some extent. However, this still doesn’t solve the equipment centralization issue and, ironically enough, there are actually concerns around the mining pools themselves becoming too large or quasi-centralized.

That said, the second point to keep in mind about potential mining centralization is that the large centralized players don’t pose a serious threat to Bitcoin or its decentralization. This is because the nodes (the computer systems and software anyone can easily run at their own home and the most decentralized part of the Bitcoin network) are ultimately the ones in charge of upholding the integrity of transactions.

The Bitcoin miners secure the network with the energy they expend and technically approve transactions, but they can only earn block rewards if the majority of the nodes say the transactions they approve are valid. So miner approvals have to be approved, and this offers a healthy system of checks and balances within the network.

Another key quality to keep in mind about PoW and especially about Bitcoin is adding money to the supply requires real costs. In fiat and PoS systems, money can be printed at will with a stroke of a keyboard. There might be political or even programmatic constraints to money supply increases, but there are technically no real constraints like physical resources required to mint the new money.

Adding more gold or bitcoin to the overall supply, on the other hand, takes a lot of effort and energy. In other words, creating money in PoW systems isn’t cheap, let alone free. If you want to create money, you have to put in the work, which means expending real resources like energy, which, in turn, means no person, organization, or government can print money purely at their own discretion. And that usually proves to be a valuable quality when limiting the extent to which human greed starts to take hold of fiscal and monetary policy.

So, just to summarize, the Bitcoin PoW system uses a decentralized network of miners (specialized computers) that expend energy to solve cryptographic puzzles, and the winner gets to approve the next block of transactions on the blockchain. If the nodes accept the transactions miners approve, the miners earn the block reward that reimburses them for all the energy they use.

Alright, I’ll circle back to recap and expand on some of the most important points about PoW toward the end, but let’s transition to PoS.

Proof-of-Stake

PoS is the consensus mechanism most cryptocurrencies have opted to pursue as they are significantly less energy intensive, which is also another way of saying cheaper to run. Rather than expending energy to run and maintain the network with mining rigs, PoS uses a system of semi-randomly chosen validators to approve transactions. I say semi-randomly because it’s technically based on the amount those validators are staking. Just like more computing power gives you a better chance of winning a block in PoW, the more coins you stake in a PoS system does the same.

Each validator stakes some amount of the native currency, such as ETH, and they earn a return on that stake as they approve valid transactions. For simplicity’s sake, you can think of the PoS model as a security deposit. If validators approve illegitimate transactions, their stake (deposit) will be slashed, meaning they will lose money. And if they approve valid transactions, they will continue to earn the staking reward.

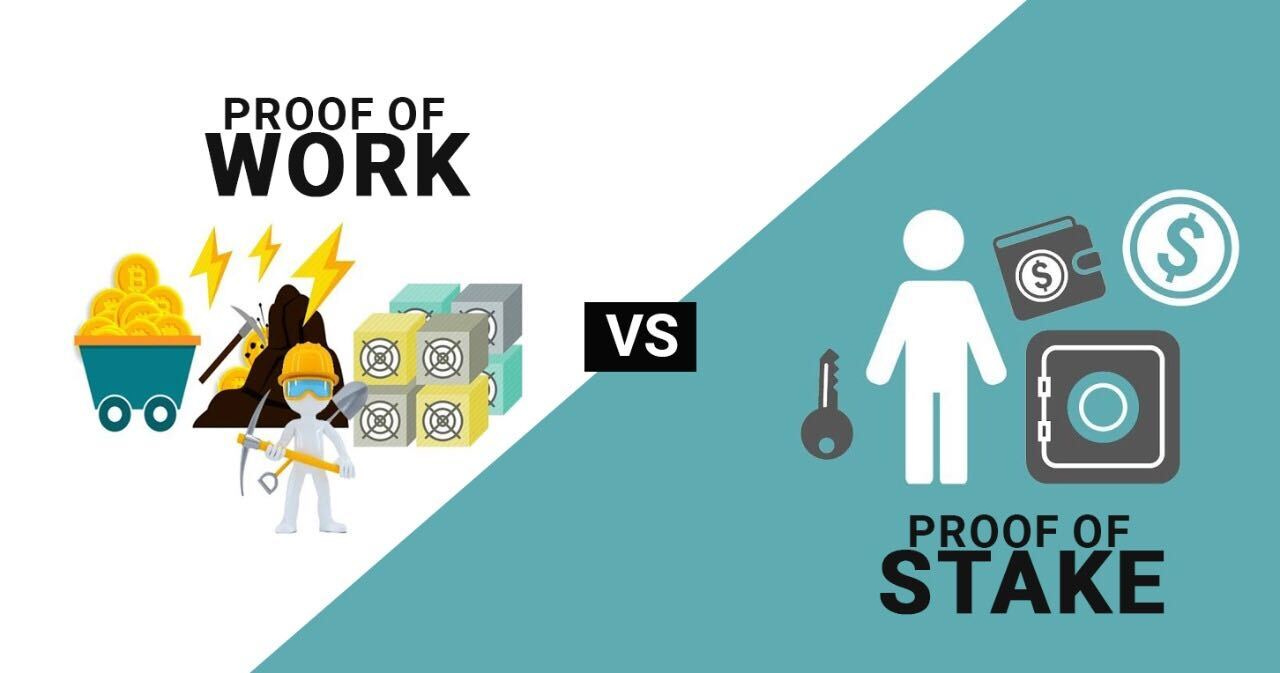

One of the key differences to focus on between PoS and PoW, then, is not the incentive structure for approving valid transactions, as they are both financial, but it’s the type of financial incentive. Instead of the active PoW approach where energy is purchased and expended beforehand through mining rigs, the PoS incentive is passive, as validators approve valid transactions or lose some of their deposit they have staked after the fact.

The PoW model is fairly simple insofar as there is no need to punish bad miners that try to validate the wrong chain or approve invalid blocks. Their punishment is simply that they spent electricity on blocks that weren’t valid and thus didn’t earn the reward to reimburse them for their efforts.

PoS, however, is a bit more complex, as there is no connection to real-world resources, but the system still needs a way to punish stakers that approve fraudulent transactions and also needs a way to ensure stakers aren’t voting on all possible chains, which can’t easily be done with PoW because it takes real resources to maintain each chain.

As alluded to, many PoS consensus mechanisms, like Ethereum, select validators based on how much of the native asset they have staked. The more you stake, the better your chance is of being selected to approve a block. In other words, the richer you are, the more you earn from staking. The validator system isn’t all that different from its mining counterpart in PoW, but PoW at least requires you to buy equipment and run a business, not simply be rich.

“Proof-of-Equity”

A crucial detail to keep in mind about PoS is how similar it is to the equity system we already have in place within the current financial system. If you think of validators who stake their assets as being equity holders, which is really what they are, the parallels become quite clear. Much like shareholders have voting powers over the direction of their respective companies, stakers in a PoS system have outsized influence over their respective protocol without anything but a large bank account.

PoS protocols reserve the security of the network to stakers and the more you stake (the richer you are), the more control over transactions you have. If it isn’t already clear by now, this isn’t exactly different from the current financial system much of crypto purports to reject, but a system of nodes, assuming they are decentralized, will help to balance out an equity-based system like this.

Equity-based systems also have a tendency to become more decentralized over time as the equity (stake) slowly distributes from the early investors with large holdings to more and more people joining the network.

Neither equity- nor staking-based systems are inherently bad, but it’s important to recognize them for what they are: systems that usually serve the wealthy before anyone else. Just like dividends and share appreciation primarily benefit the largest shareholders, the yield stakers earn and the appreciation of the native currency primarily benefit those with the largest stakes. Both models also exaggerate wealth gaps between the rich and not-so-rich equity or stakeholders.

Ethereum

Although Ethereum technically hasn’t fully transitioned to PoS, it is the face of the consensus mechanism. The suggested merge date is sometime in Q3 of 2022, so it shouldn’t be too much longer for the roadmap to become a reality. In any case, Ethereum is still largely leading the way in creating a realistic PoS system that revolves around validators rather than miners.

Once validators decide to stake ETH, they can choose how long they want to lock it up. Current stakers are locked in until Ethereum actually goes live with its PoS merge, but after that, they can opt for 3-, 6-, 9-, or 12-month lockup periods. The size of the reward you collect for your staking will also depend on the elapsed time, so there is an incentive to keep your ETH staked for as long as possible.

However, as alluded to, a somewhat disappointing quality of Ethereum’s PoS mechanism is the validator system strongly favors the very wealthy. For one, the larger stakeholders have a better chance of approving transactions and thus have a better chance of earning the staking rewards, which leads to them becoming even richer, which further increases the chance of earning fees, and the feedback loop continues, compounding their wealth well beyond the other less-capitalized stakers with the network.

The second concern with the Ethereum validator system is to be a validator, you’ll have to stake a minimum of 32 ETH, which is over $50,000 at today’s price of $1,800. However, just like individual Bitcoin miners can join mining pools to profit from the seemingly negligible amount of hash rate they contribute, Ethereum validators with next to no ETH can join validator pools to collectively reach 32 ETH and start approving blocks.

Instead of the Bitcoin version of pooling computing power, ETH holders simply pool their capital to accomplish the same thing. This doesn’t prevent the network from slowly adding more and more power to the largest stakers, but it allows anyone to earn some share of validator rewards and is far easier than the Bitcoin equivalent of purchasing an expensive mining rig and joining a mining pool.

51% Attack

One of the most commonly cited potential weaknesses of both PoW and PoS consensus mechanisms is the 51% attack, which refers to a majority of the network (at least 51%) coming together to approve illegitimate transactions. Because they control the majority of the network, they will end up approving the majority of the blocks (transactions). This sounds like a pretty simple way to corrupt the network, but it’s actually a bit more complicated.

PoW systems like Bitcoin use energy expended as their incentive for approving valid transactions and also as a means to secure the network. The more energy the network uses, the harder it is for someone to afford the energy they need to actually take over the network.

A network like Bitcoin, for example, has a huge amount of energy dedicated to securing it, so it would take billions of dollars just to afford the equipment, and then you’d have to add on all the wasted energy costs of trying to stage your attack.

And even if someone or some entity were able to seize control of the majority of the hash rate (computing power) and kept attempting to approve illegitimate transactions, they would never earn the block reward unless they approved transactions consistent with whatever all the nodes agreed was valid.

So, without all the nodes agreeing to the transactions, the corrupted 51+% would, again, just be wasting energy by not collecting the block reward. And any honest miners still in the network would be able to earn all the rewards the corrupted miners were forfeiting, so the incentive grows stronger and stronger over time for miners to act honestly and get paid, and grows weaker for bad actors that continue to waste energy costs.

A corrupted majority of miners can certainly throw a monkey wrench in the system, but they can only approve invalid transactions for as long as they can burn money. And once they’ve burned through all their cash, the valid blocks will be approved by the honest miners looking to earn the block rewards and the network will go back to functioning normally.

For these reasons, the 51% attack on the Bitcoin network is mostly overblown, though still not something to be taken lightly.

In the case of PoS systems like Ethereum, 51% attacks take a majority stake of all the staked coins. This would also amount to billions of dollars, but is hypothetically possible, especially if a number of large validators conspire to corrupt the network.

However, just like with Bitcoin, Ethereum is protected by the nodes who are the final approvers of transactions. Bad actors can fork their own chain with fraudulent transactions, but if the nodes don’t approve and honest validators keep adding blocks to the other (legitimate) chain, the corrupt validators will eventually get their entire stake slashed when they rejoin the longer chain or their forked chain is abandoned.

While it would be easier to organize all the money to orchestrate a 51% attack on Ethereum than to organize all the money, mining equipment, and energy to orchestrate a 51% attack on Bitcoin, it’s easier to slash someone’s stake than to stop them from controlling 51% of the hash rate.

To put it another way, getting a majority control over Ethereum or a PoS system is easier, but it can be harder to stop the majority attack in a PoW system like Bitcoin if the attacker has a seemingly endless pool of capital to throw at wasted energy (i.e. a government).

PoW & PoS Pros & Cons

Now that all this information about PoW and PoS is laid out, let’s simplify everything with a quick recap of their respective pros and cons.

First, PoW requires physical computers and energy to create new currency and approve blocks, which creates a more challenging and costly attack vector for bad actors to corrupt the network.

Another advantage of PoW systems is that creating money isn’t easy. This could be seen as a con depending on the economic theory you subscribe to, but easy money systems have a tendency to be abused by those who govern them—after all, the humans controlling the money are only human.

With actual costs and effort required to mint new coins like bitcoin in a PoW system, increasing the supply has real-world constraints. And those are in addition to the programmatic constraints dictating Bitcoin’s supply and inflation rate, though programmatic constraints like that are not guaranteed by or exclusive to a PoW system.

The last major advantage to PoW is it is much simpler in its design. As discussed in the early parts of this article, PoW is how most things get their value and is as simple as you put in work to create value. PoS systems, on the other hand, due to the complexity of creating incentives without real-world costs like energy, remain more susceptible to unique attacks, bugs, or other potential coding holes, so PoW is a bit more secure.

There are concerns that PoW miners can bounce around networks given they have no stake in any particular network, and that can lead to its own incentive problems, but, in the case of Bitcoin, for better or for worse, the specialized mining rigs make that extremely unlikely. However, the flip side of that coin is that all the specialized equipment required to run the network tends to lead to a lot of centralization in mining, especially for the manufacturers.

Another disadvantage of PoW systems is the massive amount of energy needed to secure the network can occasionally have some undesirable consequences. Most people would probably cite environmental concerns when it comes to Bitcoin’s energy use, but Bitcoin miners actually use a massive amount of wasted energy and incentivize green energy, so a more reasonable concern is how it can siphon power from grids that other sources need—Iran being a prime example when it banned Bitcoin mining to avoid power shortages.

As for PoS, the greatest advantage is, ironically, that it doesn’t require energy or expensive equipment to run the network. Many Bitcoiners would probably argue that’s a weakness because it might misalign incentives and jeopardize security, but there are some concerns with PoW consuming so much energy.

I already mentioned the potential for energy hoarding at the expense of other power needs, but additional concerns are that specialized computer systems (ASICS) can take up a lot of valuable semiconductors, and the computers themselves often end up in landfills every 3 - 5 years when they significantly, if not entirely, breakdown.

Another advantage to PoS is that slashing is a one-and-done approach to discouraging bad actors. Once your stake is slashed, you’re out of the game. With PoW systems, however, once you have 51% control, you can theoretically keep attacking the network as long as you want, though you would be wasting huge amounts of energy to continue doing so. Nobody can slash your mining rigs, so even though you would be wasting boatloads of money, you could continue to frustrate the network if you had the money to waste.

Now, in terms of weaknesses, one of the most commonly cited for PoS systems is the pre-mine, which refers to the coins given out to developers or early investors. In PoW systems, the money supply is earned and released over time by mining, but most PoS systems give out a large portion of the supply in the beginning to help get the project off the ground. The issue with that is it leads to a lot of centralized power and excessive distribution inequality.

Most PoS systems have an inflation rate that adds new money into existence to spread across the ecosystem, but a significant plurality of the supply will usually be concentrated among a small handful of lucky investors who were part of that system’s pre-mine handout.

All that being said, the main takeaway to draw from all these pros and cons is the strengths of both consensus mechanisms have unique weaknesses that come with them, or put another way, the weaknesses are usually part of a trade-off for some reasonable benefit. In that sense, then, each consensus mechanism can be better or worse at meeting different goals, so you’ll have to weigh and consider what strengths or shortcomings are the most important to you.

Conclusion

PoW is generally a more secure consensus mechanism with real-world costs that create a healthier system of constraints and alignment of incentives, but all the equipment and energy they use will also have real-world consequences, one of which is a larger barrier to entry for becoming a miner, the PoS equivalent of a validator.

The final point worth underscoring in this battle between PoW and PoS is both Bitcoin and Ethereum have unique characteristics that are not exclusive to either consensus mechanism. Many people view the debate between the two consensus mechanisms as synonymous with Bitcoin vs Ethereum, but some of the best qualities of both have nothing to do with the consensus mechanisms.

As an example, the 21M hard cap on the Bitcoin supply is a programmatic constraint any blockchain network can have, including PoS systems. High transactions per second is another example of something a PoW system could have despite its common association with PoS. Transactions per second have to do with the block size. The larger the block the more transactions per second, but that can lead to more centralization among the nodes because considerably more storage is required, which isn’t necessarily attainable for the average person.

Bottom line, PoW vs PoS is not the same as Bitcoin vs Ethereum. Both consensus mechanisms have various strengths and weaknesses, but each blockchain also has its own strengths and weaknesses that have nothing to do with the consensus mechanism it uses.

So, to put a bow on things and wrap all this up, PoW and PoS have very different ways of accomplishing the same thing (consensus for approving transactions), but the most important qualities of a network are usually the programmatic ones like total supply, block size, or even just use case.

Understanding the different consensus mechanisms and how they relate to each respective blockchain is an important first step, but viewing each blockchain through the lens of its unique characteristics is ultimately what really matters.

Share this post