Currency Pegs

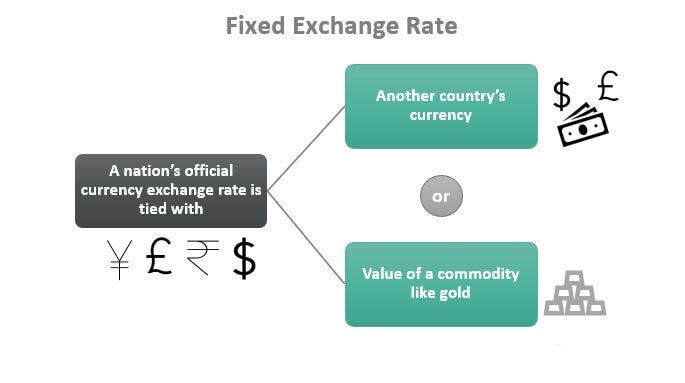

A currency peg is when one country aims to maintain a fixed (or roughly fixed) exchange rate between its currency and another currency, which could be a commodity like gold or a government-issued currency. The purpose of this is to stabilize exchange rates between trading partners (the two currency issuers), which makes trade easier and more predictable, but it also allows a country to keep the value of its currency lower than if it were to use a floating exchange rate.

Trying to keep the value of one’s currency low may sound counterproductive on its face, but it’s a way to make a country’s exports more competitive relative to the country to which it’s pegging its currency, which is usually the United States (the biggest importer). By pegging one’s currency to the dollar, a country promotes anti-competitive trade with the US and creates an easier path toward maintaining a trade surplus, which ties into Triffin’s Paradox and the global demand for dollars.

When a country pegs its currency to another, even if done with the sole purpose of keeping its value weak relative to that other currency, it generally won’t want its currency to weaken too much. An excessively weak currency can put serious constraints on crucial imports, lead to widespread inflation, or spark a whole host of other economic problems.

This is why any country pegging its currency to another will usually commit to some minimum exchange rate it’s willing to defend. However, because it doesn’t have the ability to print the other currency, defending that peg requires spending the reserves it holds in that currency. So, if that country’s currency weakens because of a lot of capital outflows, it will have to sell its reserves of the other currency to buy its own currency (assets denominated in its currency) to maintain that peg and avoid a rapid devaluation.

On the flip side, if a country that pegs its currency to another has a lot of capital inflows, meaning a strengthening currency, it will have to devalue its currency by printing more and buying assets denominated in the currency to which it’s pegged. If the country doesn’t devalue, its currency can break the peg through rapid appreciation, which would be very counterproductive to trade by making its exports very uncompetitive.

The most famous example of a currency peg (and its break) is from 1992 when the Bank of England (BOE) couldn’t maintain the pound’s peg to the Deutschmark. At the time, the BOE was dealing with considerably higher inflation than Germany, which drove most people away from the pound and into the Deutschmark.

To combat those capital outflows putting pressure on the exchange rate and peg, the BOE raised interest rates to the teens to attract investors, but speculators like George Soros jumped into short the pound once it became clear how much the BOE was losing with those higher rates, which did little to encourage investors anyway. Eventually, the BOE couldn’t afford to maintain the peg, the pound rapidly devalued against the Deutschmark, and George Soros walked away with $1B in profit.

The breaking of currency pegs is by no means a common occurrence, but knowing which countries maintain a peg and how much in reserves and resolve they have to defend that peg are important when assessing the full scope of risk or opportunity (in the case of Soros) in foreign exchange rates.

Share this post